Cyberweekly #246 - Walking the floor as a leader

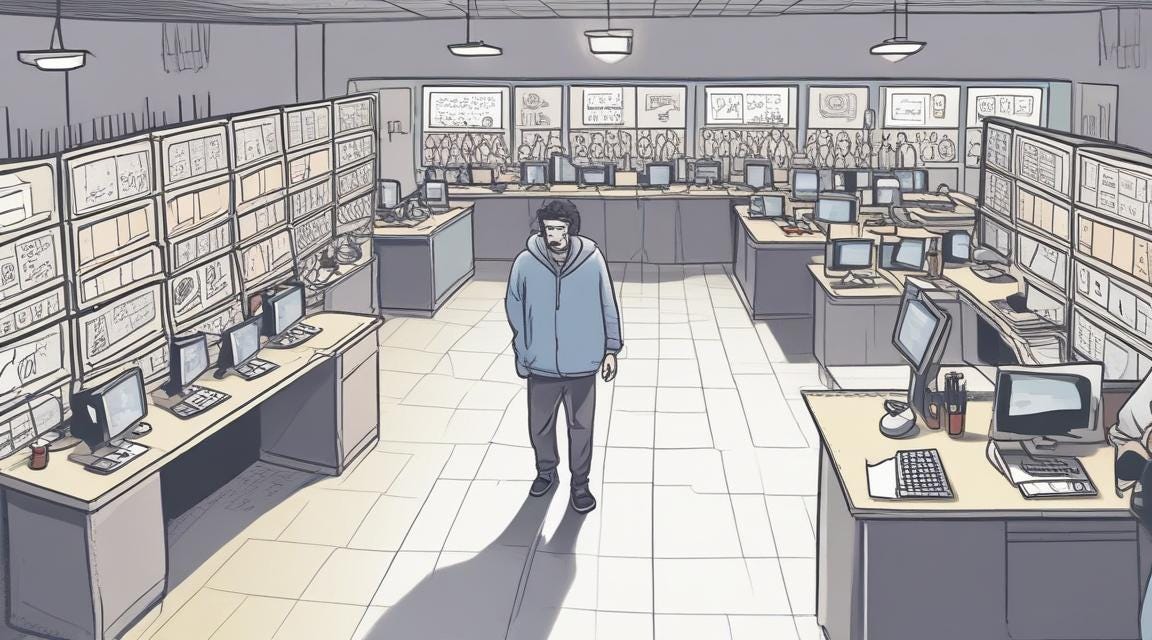

After last weeks newsletter, I was contacted by a few people to mention that the combination of pieces about "moving away from the shop floor" resonated quite strongly with them.

It's really hard when you work in cybersecurity to even work out where your shop floor is. In many modern organisations, your teams may not work in the same room, building or even city. Teams are increasingly distributed, which is great for individuals work life balance, but as a leader means it's much harder to easily pop in, observe team working or even just get a sense of the hubub around the floor.

One of the attitudes that constantly mystifies me in senior leaders is a reluctance to embrace more modern communication systems, or a failure to recognise what they are and represent. That slack instance, especially the channels with all the gifs, the jokes, the constant stream of banter... that's your employees talking to one another, complaining at the water cooler, and discussing their daily work and frustrations. If you want to take the temperature of your organisation you are going to need to dip your toes into these medium to be able to listen to the overall hubub and noise and look for patterns that matter to you.

I get that some leaders are uncomfortable because they feel that there's just too much to monitor. Others might feel that joining channels might make people change their behaviours. Others simply don't send messages that way and don't understand how others do communicate that way. But whether it's discoverable teams channels, slack random channels, or your internal team Yammer instance, you need to be where your staff are and be able to sample and test the tone of that conversation.

For almost every digital team that I've worked with, those core communication channels, and the digital equivalents of postits on walls, your trello, jira, asana, whatever, are where the information about what's working and not working is visible for display. In my early days in agile, we used to walk other teams boards occasionally to get a sense of work cards that hadn't moved, the type of work that was completed so we could draw some inferences from the stuff being displayed. These digital channels are where people are bringing their real self to work.

And of course, it's not about the details, nobody needs you to spot a specific individual problem and reach down and fix it, in fact if you do that, depending on your seniority, you may well freak people out. But being aware of whats being discussed, prioritised, raised as blockers can be incredibly valuable information to help you make sense of the more formal reports coming up to you. Is your strategy actually on track? Do people use the words from your vision statement and mission when defining their work goals? Do people care about the newest product release or culture change that you are driving? What people do and don't talk about tells you a huge amount about the culture that you are actually creating compared to the one in your head that you think you are setting.

As Chris Matts, the IT Risk Manager, says this week, senior leadership have to reach down to hear about the truth on the factory floor. The power structures and incentives in most organisations make it incredibly difficult for more junior people to actually go over their bosses head to report up things that worry or concern them.

“Reaching up” in a failureship culture | The IT Risk Manager

A common behaviour in organisations is for people to use the resources of the organisation to benefit their career at the expense of the organisation. A manager with one or more teams might divert resources to work on a “shadow backlog” in order to gain favour with a powerful stakeholder who should not have access to those resources. The manager controlling the resources in effect can benefit from building a stronger relationship with a powerful stakeholder (behave badly) by the misallocation of resources because the senior leadership has no visibility of the gemba. If a person on the gemba attempted to alert senior leadership of this activity, they are the only people who can see it after all, their career within the organisation would be at risk as they would not only upset their direct management, but also the manager’s powerful stakeholder. Obviously at some point the investment will be revealed to the organisation, however the goal is to hide the investment long enough so that the “sunk cost” is big enough that the next level up in the organisation cannot stop the investment without them appearing incompetent, with an organisation that is “out of control”.

Leaders need to create an “Andon Cord” so that workers at the Gemba can signal that the organisation has moved from safety and needs to stop so that it can move back to safety.

[…]

Those working on the Gemba CANNOT REACH UP SAFELY in a risk averse failureship culture. Leadership need to reach down by collapsing the power distance index and by creating a number of “Andon Cords” so that those working at the Gemba can invite the leadership to go to the Gemba.

I really like this, and it’s a useful reminder about the value of walking the shop floor, just as I said last week

S3 Bucket Encryption Doesn't Work The Way You Think It Works

Wait… Why can we read the contents of the file if it’s encrypted?

The answer is in the type of encryption used – server-side encryption with Amazon S3 managed keys (SSE-S3). All of the encryption operations happen transparently, without the need for the user to perform encryption or decryption operations explicitly.

This is where common understanding starts to diverge from reality. If an attacker has access to an s3 bucket that’s using the default encryption, they won’t ever see or interact with the encrypted version of the file. They can just smash the download button, and get the clear-text copy.

Compliance ✅

[…]

What happens if an organisation does something more sophisticated than just the default?

Much of the encryption magic inside AWS happens around the Key Management Service (KMS) . AWS services that use KMS keys to encrypt resources often create keys for you. KMS keys that AWS services create in an AWS account are AWS managed keys .

Damnit… we didn’t even have to specify the key. It’s still all magic. This is awkward.

What’s missing? Well, we can decrypt the file because we have access to the KMS key we created. Duh!

A wonderfully written reminder that “encryption at rest” is often a compliance line item that makes very little difference against a lot of attacks.

In this case, the encryption is protecting against a whole selection of “out of band” attacks, ranging from a malicious employee stealing a hard disk, to a misconfiguration that results in your bits on the hard drive being sent to another customer.

However, if the file/system/thing is accessible through the customer interface, then the encryption is almost always invisible, and thus any attack that compromises the normal flow, the encryption won’t do anything.

That’s good, it means that your abstractions don’t leak, but when someone insists on encryption at rest, be sure to check what sort of attacks they think it’s protecting against

GitHub comments abused to push malware via Microsoft repo URLs

Yesterday, McAfee released a report on a new LUA malware loader distributed through what appeared to be a legitimate Microsoft GitHub repository for the "C++ Library Manager for Windows, Linux, and MacOS," known as vcpkg . The URLs for the malware installers, shown below, clearly indicate that they belong to the Microsoft repo, but we could not find any reference to the files in the project's source code.

https://github[.]com/microsoft/vcpkg/files/14125503/Cheat.Lab.2.7.2.zip https://github[.]com/microsoft/STL/files/14432565/Cheater.Pro.1.6.0.zipFinding it strange that a Microsoft repo would be distributing malware since February , BleepingComputer looked into it and found that the files are not part of vcpkg but were uploaded as part of a comment left on a commit or issue in the project.

When leaving a comment, a GitHub user can attach a file, which will be uploaded to GitHub's CDN and associated with the related project using a unique URL in this format: ' https://www.github.com/{project_user}/{repo_name}/files/{file_id}/{file_name}. ' Instead of generating the URL after a comment is posted, GitHub automatically generates the download link after you add the file to an unsaved comment, as shown below. This allows threat actors to attach their malware to any repository without them knowing.

Even if you decide not to post the comment or delete it after it is posted, the files are not deleted from GitHub's CDN, and the download URLs continue to work forever.

In the words of one cybersecurity expert I know, “Oh no!”.

This is one of those design decisions that’s hard to see the impact until it gets exploited, but Microsoft need to work out how to fix this without breaking years of legacy URLs.

If there’s a general lesson to learn from this, it’s always make sure that user generated content lives in an obviously user generated URL structure so it can’t be mistaken for corporately generated content

Unearthing APT44: Russia’s Notorious Cyber Sabotage Unit Sandworm | Google Cloud Blog

To date, no other Russian government-backed cyber group has played a more central role in shaping and supporting Russia’s military campaign.

Yet the threat posed by Sandworm is far from limited to Ukraine. Mandiant continues to see operations from the group that are global in scope in key political, military, and economic hotspots for Russia. Additionally, with a record number of people participating in national elections in 2024, Sandworm’s history of attempting to interfere in democratic processes further elevates the severity of the threat the group may pose in the near-term.

Given the active and diffuse nature of the threat posed by Sandworm globally, Mandiant has decided to graduate the group into a named Advanced Persistent Threat: APT44 . As part of this process, we are releasing a report, “ APT44: Unearthing Sandworm ”, that provides additional insights into the group’s new operations, retrospective insights, and context on how the group is adjusting to support Moscow’s war aims.

I hadn’t really realised that Mandiant hadn’t actually given Sandworm an APT moniker. Given the group has inspired several books, hundreds of articles and threat intel reports and the plots of many books, tv shows and movies, I had assumed that this group was almost one of the definitions of an advanced persistent threat.

Eitherway, this new report which summarises their activity, especially as an aid to military operations is a fantastic read, and reminder of the goals, aims and capabilities of some of these advanced attackers

Director Wray's Remarks at the Vanderbilt Summit on Modern Conflict and Emerging Threats — FBI

The PRC has made it clear that it considers every sector that makes our society run as fair game in its bid to dominate on the world stage, and that its plan is to land low blows against civilian infrastructure to try to induce panic and break America’s will to resist.

We’ve been countering this growing danger for years now. China-sponsored hackers pre-positioned for potential cyberattacks against U.S. oil and natural gas companies way back in 2011. And while it’s often hard to tell what a hacker plans to do with their illicit network access—that is, theft or damage—until they take the final step and show their hand, these hackers’ behavior said a lot about their intentions.

When one victim company set up a honeypot—essentially, a trap designed to look like a legitimate part of a computer network with decoy documents—it took the hackers all of 15 minutes to steal data related to the control and monitoring systems while ignoring financial and business-related information, which suggests their goals were even more sinister than stealing a leg up economically.

That was just one victim, and we tracked a total of 23 pipeline operators targeted by these actors.

More recently, you may have heard about a group of China-sponsored hackers known as Volt Typhoon. In that case, we found persistent PRC access in our critical telecommunications, energy, water, and other infrastructure sectors. They were hiding inside our networks, using tactics known as “living-off-the-land"—essentially, exploiting built-in tools that already exist on victim networks to get their sinister job done, tools that network defenders expect to see in use and so don’t raise suspicions—while they also operated botnets to further conceal their malicious activity and the fact that it was coming from China. All this, with the goal of giving the Chinese government the ability to wait for just the right moment to deal a devastating blow.

[…]

So, to take the PRC’s Microsoft Exchange compromise as an example, we leaned on our private sector partnerships, identified the vulnerable machines, and learned the hackers had implanted webshells—malicious code that created a back door and gave them continued remote access to the victims’ networks. We then pushed out a joint cybersecurity advisory with CISA to give network defenders the technical information they needed to disrupt the threat and eliminate those backdoors.

But some system owners weren’t able to remove the webshells themselves, which meant their networks remained vulnerable. So, working with Microsoft, we executed a first-of-its-kind surgical, court-authorized operation, copying and removing the harmful code from hundreds of vulnerable computers.

And those backdoors the Chinese government hackers had propped open? We slammed them shut so the cyber actors could no longer use them to access victim networks.

This was a fascinating set of public remarks from the director of the FBI, not only on the size and bredth of the activity that they see and attribute to China, but also because of the acknowledgement of this new tactic of gaining specific legal authority to use the same vulnerabilities the attackers use to get onto systems and patch them, preventing the vulnerability being exploited.

It’s still a weird concept, one we often aliken to your local police officer wandering down your street, checking your doors and then locking them for you if you forgot. But in a modern digital world, making modifications to your system without you knowing feels like it carries a significant risk. Of course, it’s a much worse impact if you get compromised, so maybe it’s a bit swings and roundabouts

State of DevSecOps | Datadog

FACT 3 Only a small portion of identified vulnerabilities are worth prioritizing In 2023, over 4,000 high and 1,000 critical vulnerabilities were identified and inventoried in the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) project . Through our research, we’ve found that the average service is vulnerable to 19 such vulnerabilities. However, according to past academic research , only around 5 percent of vulnerabilities are exploited by attackers in the wild.

Given these numbers, it’s easy to see why practitioners are overwhelmed with the amount of vulnerabilities they face, and why they need prioritization frameworks to help them focus on what matters. We analyzed a large number of vulnerabilities and computed an “adjusted score” based on several additional factors to determine the likelihood and impact of a successful exploitation:

Is the vulnerable service publicly exposed to the internet?

Does it run in production, as opposed to a development or test environment?

Is there exploit code available online, or instructions on how to exploit the vulnerability?

We also considered the Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS) score, giving more weight to vulnerabilities that scored higher on this metric. We applied this methodology to all vulnerabilities to assess how many would remain critical based on their adjusted score. We identified that, after applying our adjusted scoring, 63 percent of organizations that had vulnerabilities with a critical CVE severity no longer have any critical vulnerabilities . Meanwhile, 30 percent of organizations see their number of critical vulnerabilities reduced by half or more .

There’s some interesting stats in this breakdown, and I was relaly interested in the large number of orgs (at least 38% in Datadogs survey) that still had “ClickOps” in their cloud environment. But that aside, I thought this analysis of vulnerabilities was interesting.

We frequently see calls to patch early, patch often and about some critical CVSS 9.6 vulnerability that you must drop everything to patch. But those scores simply don’t take into account the context, such as the questions below. I’d not seen the EPSS before, and while I like some of the concepts, it smells a little of “throwing AI at the problem”. It’s also a value that will change over time, so taking into account whether the exploit is available in common tools, whether it’s discussed on social media can all weigh into how seriously you should consider patching, it’s a score that might be different today to tomorrow, and that makes making a patching policy based on it hard.

But it’s still true that a CVSS score of 9.6 can be on an airgapped system, that has that feature disabled, and thus not be critical to patch. It’s worth remembering that the severity of the vulnerability is only one input to the decision process for patching

Fixing Typos and Breaching Microsoft’s Perimeter – John Stawinski IV

GitHub recommends against using self-hosted runners on a public repository , as misconfigurations could allow external attackers to compromise the runners and gain a foothold in the organization’s infrastructure or tamper with subsequent builds. Instead, GitHub recommends using GitHub-hosted runners, which are available for free (up to a limit) to all GitHub repositories.

It is possible for an organization to securely use self-hosted runners on a public repository if the runners are ephemeral, isolated, and permissions are locked down . Where did Microsoft Go Wrong? Microsoft violated all of the guidelines I just laid out. They used a domain-joined workstation as a non-ephemeral, self-hosted runner on the public DeepSpeed repository. Essentially, an employee took one of their computers and offered it up to everyone on the internet.

Many of our other attacks, like our attack on PyTorch , required implantation, reconnaissance, crazy token pivots, and secret stealing to prove impact. With DeepSpeed, all we had to do was get RCE and we had breached one of the largest organizations in the world. By default, when a self-hosted runner is attached to a repository, any of that repository’s workflows can use that runner. This setting also applies to workflows from fork pull requests. The result of these settings is that, by default, any repository contributor can execute code on the self-hosted runner by submitting a malicious PR.

A reminder here of how important it is to pay attention to some of these warnings. Github recommends against using self-hosted runners, but people do it anyway.

This sort of CI/CD poisoning attack is being increasingly documented by security researchers and it won’t take too long before it’s weaponised by malicious actors.

The only saving grace in most of this is that actually carrying out the attack requires creating public pull requests, which creates an audit log of your work and increases the detection possibility, but as you’ll see if you read the report, it’s not easy and often not a monitored part of most organisations tool chains

The invasive Otter

Today I was in a meeting and my name showed up as Amy Otter Pilot. This was alarming to me because I was not aware of having an Otter subscription. Apparently, I had a free account because of my curiosity when I was sent a meeting recap from another person. I clicked to see what this was all about. But in today’s meeting, a person I met with was sent a meeting recap from “me”. Otter had joined a meeting that I was invited to and then emailed them that person a recap of our meeting. I was very disturbed by this event.

I don’t have an Otter app installed on my computer, nor is it a browser extension, nor is it an add-in for Outlook. So how is it doing this?

[…]

Click on your account and select Account Settings. Look to the bottom on the main panel to find the Delete account option. Once you click to delete your account, you are asked to authenticate. Do that and then your account will be deleted from the Otter account page. Part 2: Unfortunately, deleting your account from Otter does not revoke its permission to your mailbox. Otter installs itself as an OAuth app in your network but does not remove itself.

This feels deeply disturbing. The use of tools that make it easier to take meeting notes is rapidly going to become a fact of life, and there may not be a lot we can do about it except for accepting that our meetings are being recorded. (For public figures, this might mean that all video calls need to be consdiered “on the record” as if they’re transcribed, they’re almost certainly legally admissable, subject to legal holds, and in public, subject to public records acts of various forms).

But far worse here is the behaviour of an org that not only joins meetings, but does so almost silently without warning the other participants, and does so in a way that even deleting your account with them doesn’t stop it accessing your meetings? That feels like it’s well overstepping the bounds of what most people consider acceptable. I note that if you are a Microsoft 365 administrator, you can prohibit your users from granting any OAuth access, which of course means you need to handle every request for a new app that does need access speedily and easily, or accept that your staff cannot enhance their office experience. You can also prohibit specific apps, and this might be worth deciding as an org whether it’s one for your prohibition lists

PuTTY vulnerability vuln-p521-bias

very version of the PuTTY tools from 0.68 to 0.80 inclusive has a critical vulnerability in the code that generates signatures from ECDSA private keys which use the NIST P521 curve. (PuTTY, or Pageant, generates a signature from a key when using it to authenticate you to an SSH server.) This vulnerability has been assigned CVE-2024-31497 .

The bad news: the effect of the vulnerability is to compromise the private key . An attacker in possession of a few dozen signed messages and the public key has enough information to recover the private key, and then forge signatures as if they were from you, allowing them to (for instance) log in to any servers you use that key for. To obtain these signatures, an attacker need only briefly compromise any server you use the key to authenticate to, or momentarily gain access to a copy of Pageant holding the key.

[…]

PuTTY's technique worked by making a SHA-512 hash, and then reducing it mod q , where q is the order of the group used in the DSA system. For integer DSA (for which PuTTY's technique was originally developed), q is about 160 bits; for elliptic-curve DSA (which came later) it has about the same number of bits as the curve modulus, so 256 or 384 or 521 bits for the NIST curves.

In all of those cases except P521, the bias introduced by reducing a 512-bit number mod q is negligible. But in the case of P521, where q has 521 bits (i.e. more than 512), reducing a 512-bit number mod q has no effect at all – you get a value of k whose top 9 bits are always zero.

This bias is sufficient to allow a key recovery attack. It's less immediate than if an attacker knows all of k , but it turns out that if k has a biased distribution in this way, it's possible to aggregate information from multiple signatures and recover the private key eventually. Apparently the number of signatures required is around 60.

The good news is that this only affects a tiny proportion of keys because it’s not a common combination of curve and key generation mechanism.

But also a useful reminder that in a 521 bits, which is to say a number between 0 and 2 to the power 521 (which is 6.8 with 156 0’s on the end), if it has just 9 bits at the end that are always 0, which is in essence a rounding error, then you can reconstitue the key with shockingly little information.

Cryptographic errors leak in really non-intuitive ways, and this is why you should never write your own mathmatical or cryptographic implementation unless you know what you are doing and have people to check it.

Putty authors knew what they were doing, and their implementation formed the basis for a standard in this space, and still they made an error of assumptions early on that resulted in this mistake.

Thanks for reading

Michael